Contact details

Foundation for Industrial History of Győr

Szent István út 10/a

Phone:

+3696520274

Fax: +3696520291

E-mail:

ipartortenet@ipartortenet.hu

Map

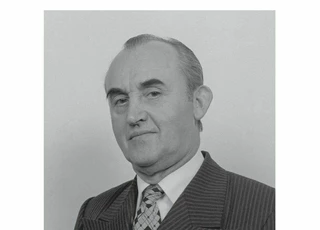

Ede Horvath

The “Red Baron of Győr”. Ede Horváth (1924 – 1998)

"I loved this factory. It was my life."

“I never demanded to be loved at work

… to be accepted at work and given

the same respect that I give to others.”

"I can't

imagine an economic-productive democracy."

I wanted something, and anyone who wants something in Hungary

is viewed with suspicion at first, and later with envy.

Instead of acknowledging, they ask him in a hostile manner how he did it:

instead of imitating, they criticize him.”

(Ede Horváth)

Ede Horváth was born in Szombathely on September 18, 1924. He had seven siblings, three older and three younger, and he was the fourth in line. He lost his mother at a young age, so his father raised the large family that moved to the Győr area in the 1930s amidst great difficulties. The head of the family got a job in the wagon factory's blacksmith shop. His maternal grandmother, who was of Swabian origin, lived in Törökbálint. Ede lived with her and went from there to work in Kőbánya when the wagon factory's aircraft department was relocated to the brewery's cellars due to the bombings. His mother's siblings and relatives were deported to southern Germany after World War II because of their Swabian origin.

Ede Horváth attended elementary school in Szombathely. From the age of second grade, he attended the city's boarding forest school. After graduating, he became an apprentice turner at the Győr wagon factory. He acquired theoretical knowledge about the profession at the Kossuth Lajos Street city apprentice school. After receiving his assistant's letter, he started working as a turner in the car department of the wagon factory. In the spring of 1945, he hid from deportation to Germany with his father living in Gecsé and his brother working in Bük. When peace came, he returned to Győr and worked again in the car department of the wagon factory.

In the autumn of 1949, he joined the competition for the title of the best worker in the profession, the culmination of which was the shift announced for Stalin's 70th birthday. Ede Horváth gained national fame with the sensational result achieved under artificial conditions during the Stalin shift on December 21, 1949. He lived for the rest of his life in the house in Ménfőcsanak, the plot of which he bought with the Kossuth Prize he shared with Imre Muszka in 1950.

He was quickly promoted from the workbench and first became a middle manager of the car factory, then in 1951 – at the age of 27 – he was appointed director of the Győr Machine Tool Factory. The military plant operating on the site of the former Győr Cannon Factory was entrusted with the production of the carriage structures of 37 and 85 mm anti-aircraft guns. Over the course of a few years, with persistent work, ingenuity and many conflicts, he developed the former Győr plant of MÁVAG into one of the most organized and modern plants in the Győr industry. In October 1956, he was also replaced by the factory's workers' council, worked briefly in Székesfehérvár, and was then reinstated in his function after János Kádár came to power. He devoted most of his energy to ensuring a stable livelihood and regular employment for his employees, even while the factory's profile was constantly changing. The production of military products temporarily ceased after 1956, and the director tried to use up production capacities by manufacturing tractor trailers, hydraulics, combine harvester straw collectors, motorboat engines, and diesel-electric locomotive drive motors and main dynamos. The Gearbox Factory, which had been wedged into the area of the wagon factory, was relocated to one of the vacant halls of the Machine Tool Factory at the end of 1960. From then on, the factory's main profile became the production of rear and front axles for trucks (including the four-wheel drive Csepel D-344) and buses. In 1961, the Ministry of Metallurgy and Mechanical Industry entrusted the Győr Machine Tool Factory with the coordination of the work of one and a half dozen suppliers involved in the production of armored amphibious combat vehicles.

On May 20, 1963, he was appointed CEO of the wagon factory named after the East German communist politician Wilhelm Pieck, despite the fact that most of the members of the county party committee did not agree with this. He became the number one manager of the wagon factory and also held the position of director of the Machine Tool Factory until January 1, 1964. At that time, the two large Győr ironworks were merged into one large company under the name Wilhelm Pieck Járműipari Művek.

He did not apply to be a Stakhanovite. He was asked when the previously selected worker did not work out. But he did not scramble for the director positions, especially not by trampling over others. It was not he, but János Porubszky, who was the first director of the Tool Machine Factory, who resigned after a few months because he was unable to cope with the thousands of difficulties of starting the factory. Despite having more than a decade of managerial experience behind him, the county first secretary Ferenc Lombos selected Antal Gőgitz, a former car mechanic at a wagon factory and trade union leader, as Albert Lakatos's successor. Only when Gőgitz resigned did he agree, on the strong recommendation of Gyula Horgos, the Minister of Metallurgy and Mechanical Industry, to make Ede Horváth the CEO of the wagon factory.

The new CEO thoroughly reorganized the wagon factory, centralized management, merged departments and organized new departments. In accordance with the principle applied in the Győr Machine Tool Factory for almost a decade, he grouped the machines not according to machine types , but according to the logic of production . The constant reorganizations, which aimed at producing products cheaper and more efficiently, remained on the agenda for several years and ruffled people's spirits. The new CEO did not hesitate to fire people if necessary. There were great uncertainties and discussions regarding the future and development path of the factory. The measures that often brutally violated the existential interests of those involved could not have been implemented with the paternalistic management style typical of the previous CEO. Unlike his predecessor, he never allowed the factory party and the trade union committee to dictate production and personnel matters. He did not hold fruitless meetings for hours, he did not discuss problems, but gave orders and whoever did not carry out his orders was summarily fired from the factory or made sure that he resigned himself. This certainly led to the fact that after his appointment as CEO, his subordinates tried to overthrow him with illegal actions. The myth developed around Ede Horváth that he could do anything if the economic results were good, the leader could not be removed. In the autumn of 1964, unknown perpetrators called on the technical managers of the wagon factory to strike, to “sabotage”. The action was intended to get the top management to fire Ede Horváth due to the failed economic performance. They did not achieve their goal, Horváth remained the number one manager of the factory until 1989.

He wanted to decide everything himself, even the smallest, routine daily matters. He did not tolerate contradiction, he demanded that his subordinates unconditionally carry out his instructions even if they turned out to be unnecessary, pointless, or even downright harmful. He explained this principle, which was difficult to defend and often resulted in losses in practice, by saying that this was the only way he could get real feedback on the consequences of his decisions, for which he always took personal responsibility, regardless of their effectiveness. He was impatient, wanted to achieve results immediately, and expected everyone to work at the same speed as he himself. He set higher standards for himself than even his colleagues, he was considered a workaholic, a "workaholic", who did not take a vacation for years, spent 12-14 hours in his office, his secretaries worked two shifts with him, often visited the factory on Sundays, kept his trips abroad as short as possible and when he returned home, he would first go to work and only then go to his family. If he saw a mistake somewhere, or if things did not go as he expected, he would pull himself together in a moment and in an indescribable tone, dismiss those he thought were guilty. He does not excuse his impatience, his rude style, and his rude treatment of his subordinates, but he explains it somewhat by the fact that he worked under constant pressure and undertook tasks that others would have avoided and that could have easily been taken.

Ede Horváth's private life was impeccable. He lived an exemplary family life, had no affairs with women, almost never drank alcohol, did not hunt, did not gamble and could not be corrupted by anything. His opponents could hardly find fault with him. All they could bring against him was that he sometimes used an unacceptable tone towards his colleagues and surrounded himself with people who were outside the party and could be blackmailed because of their past, and that he did not ask for the opinion of the factory party and trade union in matters in which the socio-political organizations had the right to intervene, give opinions, and in some matters even have the right to veto. He was maniacally fond of order and cleanliness, and was always elegant and pedantic in both his work and appearance. He demanded this from others, which he sometimes expressed in a way that was difficult to accept. It is a fact that there were few leaders in Hungary who attached similar importance to the social welfare of workers, a cultured locker room, a bathroom, a place to eat, and clean work clothes.

It is often claimed that Ede Horváth's leadership style and practice were in direct conflict with the (pseudo)humanist principles attributed to the socialist system. In reality, however, he had the courage to implement in practice what the state party demanded, namely that some economic leaders did not yet demand order and work discipline, and would tolerate disorganization and poor quality. This also contributed to his frequent conflict with his colleagues and the county and national party leadership. Due to his objectionable behavior and certain irregularities, he received a reprimand in 1962 and a strict reprimand in 1965. During the discussion of his second party disciplinary punishment, the Political Committee seriously considered removing him from the head of the wagon factory and even having to leave the county. This did not happen in the end, but he was removed from the Central Committee at the 1966 party congress, where he only returned in 1970. In comparison, the psychological trauma of not being nominated as a representative in the 1967 parliamentary elections caused him a more bearable psychological trauma. In 1965, party functionary Ernő Bittmann was placed in the wagon factory against the will of Ede Horváth in order to curb and limit the vehement behavior of the CEO. It was already a foregone conclusion that Horváth would be awarded the State Award in April 1970, but he had to wait 10 years for this due to the conflict that erupted with the city's former first secretary of the MSZMP at the end of 1969.

In addition to tangible successes, Ede Horváth's membership of the Central Committee and county party committees, his parliamentary representation, his membership of the county council, and the personal connections he gained largely through his political positions undoubtedly played a major role in obtaining the additional resources necessary for production.

It is often claimed that Rába was singled out because Ede Horváth was elected to the Central Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party. From the perspective of a large company's ability to assert its interests, it is clearly advantageous if its leader is a member of the highest-level political body. But the fact that someone is elected to the Central Committee does not in itself mean an absolute guarantee that the large company he or she leads will actually operate successfully and gain undeserved benefits at the expense of others. In general, a large Hungarian company did not become successful because its leader was a Central Committee member, but rather the other way around: the number one manager or party secretary of the company that brought the successes on a platter was elected to the leading party body. It was at that time that it was decided that the engine factory would be built from the largest volume of the wagon factory's history, largely non-refundable budget grants, where instead of the Hungarian-designed diesel vehicle engine, the West German MAN engine would be manufactured under license in Győr instead of Szigetszentmiklós, when Ede Horváth was under disciplinary punishment and was not a member of the KB.

In addition to the road vehicle engine, the rear axle, designed and constantly developed in Győr, became the other main product of the wagon factory, for the large-scale, automated production of which a production hall with a floor area of 28,000 and 67,000 square meters was built at the former airport, along with a whole series of auxiliary facilities (foundry, forge, tool factory) and social buildings.

The capacity of the engine factory, which started in 1969, could not be utilized initially because, despite the contracts signed, Ikarus was unable to produce enough of the new type of buses to fully utilize the engine factory's capacity. Ede Horváth did not want to hear about the fact that the production capacity of the factory, built with nearly 20 million dollars and more than 2 billion HUF loans, would be left unused. Therefore, until the production of Ikarus buses was ramped up, several thousand engines were sold to Romania alone, and Rába-MAN engines were installed in multiple-unit trains, trucks, ships, and agricultural power plants.

The most obvious way to use the Győr engines was to start manufacturing our own complete vehicles. The main units manufactured in Győr were first installed in trucks, semi-trailers, heavy and special trucks, and later, in cooperation with the American company Steiger, in heavy agricultural tractors.

In the early 1970s, MAN stopped producing the vehicle engine, the license for which it had sold to Rába, among others. Eden Horváth managed to convince the Ministry of Metallurgy and Mechanical Industry to purchase the machines that would allow the annual engine output in Győr to be increased from 13-14 thousand to 25 thousand, while at the same time producing spare parts for engines in circulation in the world and still manufactured in Győr for convertible currency. The transaction was completed, which made it possible to double the engine output.

The technical development of the Rába-MAN engines was ensured by a contract signed with the List Institute in Graz in December 1979, which was successfully concluded, but the partners were unwilling to pay the significantly higher price of the renewed engines, so only very few of these engines could be sold. Eastern European customers were satisfied with the old licensed engine.

From a quantitative and technical development perspective, the ramp-up of chassis production was more significant. The several, partly interwoven and multi-billion-dollar chassis development programs aimed at exploiting the domestic and eastern, as well as capitalist market opportunities. In the field of chassis production, Rába reached such a technical level that from the second half of the 1970s it managed to break into the markets of Western (and overseas) countries with this product.

The market expanded to the United States in 1974, when the Rába-Steiger heavy machinery production began in cooperation under the Steiger Cougar II. type tractor license. Rába initially supplied rear axles to Steiger, later IH, Eaton, and Rockwell also came forward as customers. New types of implements were needed for heavy tractors, so Rába purchased the right to manufacture modern American seeders, plows, and disc harrows. The implementation of these programs involved significant investments and the attachment of rural plants to the wagon factory. The establishment of the supply contracts with Steiger, Wauxhall, and Hesston companies (Chassis III.) and the planned cooperation with IH and Eaton (Chassis IV.) necessitated approximately 6.5 billion HUF in construction and mainly capital machinery procurement investments.

Not all of the overseas agreements worked out as originally planned. But new, promising American partners kept popping up: instead of Steiger, Eaton and IH, then Dana, then Rockwell, and the leaders of the country, which was spiraling into debt, were quick to seize any business opportunity they could get, hoping to generate dollar revenue to delay the collapse of the Hungarian economy.

The Győr Machine Tool Factory and the Gear Factory were merged on January 1, 1961, and the wagon factory and the Győr Machine Tool Factory on January 1, 1964. The rapidly increasing production profile and volume, the faltering cooperation, but most of all the labor shortage in Győr later necessitated the merger of a number of additional companies into Rába, which many after the change of regime called Ede Horváth's violent expansion, the absorption of the rural factories by Rába. Less is said about the fact that, with the exception of Pápa, new, modern halls with complete infrastructure and additional facilities were built in all units attached to Győr, and the outdated production equipment and products were replaced with Rába's advanced products and technology. More than once, the local leaders themselves have requested that Rába create stable employment for the region's workers by taking over low-efficiency plants.

In January 1984, Ede Horváth – on the occasion of his 60th birthday, which was approaching in a few months – visited Ferenc Havasi, the secretary responsible for economic policy affairs of the MSZMP Central Committee, to inquire about the party leaders’ position on his own future. At that time, the retirement age for men was 60. Havasi, authorized by the Political Committee, told him to “keep working, your work will be needed in the future”. After this, the company council formed in Rába on July 25, 1985, unanimously elected Ede Horváth as CEO. Despite the increasing economic problems in the country, the wagon factory embarked on new huge developments (a hall in Szentgotthárd, a test track in Écs, a 114,000 square meter hall), which consumed large sums of money and largely remained unfinished. Apart from the USA, all the major markets for the factory's products almost disappeared at once. The negative phenomena associated with the collapse of the socialist system (inflation of over 30%, hundreds of thousands of unemployed, a drastic drop in living standards and consumption) were subjected to undeserved attacks, and public opinion blamed the green and red barons as the main cause of the troubles. It was not in the interest of the opposition to the system to protect them, and the old men in power were busy with their own individual fates. The previously absorbed factories (especially the former Kühne) wanted to secede and therefore started to strike. Ede Horváth sensed the waves of discontent surging around him, so on October 12, 1989 - citing the fact that he still wanted to complete the ongoing investments - at the request of the company council, his soon-to-expiring mandate as CEO was extended until the end of 1992. The Győr branch of the MDF organized a strike in front of the main entrance of the wagon factory, whereupon Ede Horváth called on the directors to organize a solidarity strike alongside him and the factory. The factory directors then asked him to resign and become the honorary chairman of the factory. The CEO tore up the letter containing the offer in the presence of the chairman of the company council. On December 4, 1989, the company directors unanimously called on him to resign and retire. Ede Horváth did not accept this offer either. At the request of two members of the company council, the court annulled the council's decision of October 12, 1989, regarding the extension of Ede Horváth's position as CEO, citing a formal error. At that time, Ede Horváth finally realized that his fight to extend his status had no further meaning, so on December 17, 1989, he announced his resignation and retirement in writing. The company council dismissed him from his position on October 18, 1989. Ede Horváth died 10 days after his 74th birthday. His ashes were scattered from an airplane near the wagon factory in accordance with his request into the Mosoni-Danube. Today, his memory is only preserved by the plaque placed in the Papagáj housing estate and the Horváth Ede Memorial Committee founded in 2005,which awards the Ede Horváth Scholarship to university students and high school students studying in automotive-related majors. The plaque placed on his house in Ménfőcsanak on his 80th birthday was removed after the house was sold and demolished.

John Honvari

Attached file(s)

Back to the previous page!